In the summer of 2010 I headed 2,500 miles northward towards Telegraph Creek in the coastal mountains of northwestern British Columbia. I usually spend a month or two there at my brother’s homestead. I travel in my old Dodge van with a bed in the back. I had been on the road for eight days when I arrived at my friend Wade Davis’ summer place, an old fishing lodge on Ealue Lake (pronounced Eya-luweh by the local First Nations, meaning sky fish) in the Skeena mountains about five hours southeast of my brother’s place. I got there a few days in advance of Wade and his family. I wanted to spend that time sitting quietly. As my van came to a stop near the lake, I noticed a bird pecking away in the fire pit. Surprised, it flew up into the nearby spruce then settled again among the ashes. I knew right away it was a bird I had never seen. Grabbing my binoculars I saw for the first time a white-winged crossbill, an interruptive species whose flocks grace a lucky northerner who chances to see them. It flew off and I preceded to set up camp. During the day I sat meditating on Wade’s dock looking out at the lake.

Over the years my meditation has gotten simpler and simpler. I just sit and listen and feel the changes in wind and weather. While sitting I realized that there was fluttering behind me so I turned to watch a family of crossbills doing their odd behavior of jumping down to a cave like opening at the base of a tree and rummaging in the litter there. There was mom, dad and several fledglings. Since crossbills, as their name indicates, have crossed bills which allows them to specializes in extracting seeds from evergreen cones, I found their behavior intriguing. I assume they were hunting for insects which is often the food they feed their young. It was peaceful sitting on the dock silently watching the sun cross the sky, listening to the sounds of nature and simply being with exotic creatures like a crossbill. After a few days so spent, I thought I would take a walk over to a nearby abandoned campground. I headed out to the road, down it a short ways and then onto the rutted entrance of the old campground. My mind was quite at rest so I was very alert. The brush along the entrance was very thick. A couple of hundred feet in I stopped short noticing a large bear at the edge of the roadway. It saw me at exactly the same time I saw it but grunted in surprise. It was a beautiful gold color with dark head and extended muzzle. I thought at once, “grizzly” but wasn’t sure. I am very familiar with black bear behavior but my encounters with grizzlies are few. It clearly didn’t care for my presense and backed away into the dense brush peeking out at me. My curiosity got the better of my discretion. I looked at it through my binoculars wanting to see if it had a hump which would have confirmed it was a grizzly. So I scraped my foot on the ground. Its curiosity also overcame its fear. It returned to the edge of the road but then defied my understanding of correct behavior and kept advancing toward me. Instantly my calm vanished and I could feel my heart beating. I slowly walked backward toward the road then retreated back to Wade’s place. Given that a beeline between the campground and the lodge was a mere hundred feet of tall grass, when I returned to sitting on the dock I faced inland in the direction the bear would have come. My sitting had changed.

Although in modern garb this sort of experience was central to the practice of many forest monks in the millennia after the Buddha. They left the civilized world to face life and death in the wilds. Their sojourns became the stuff of myth, canonized by their monastery brethren. The reality of their experiences was somewhat different. This reality can be excavated from the stories told about them but also from journals, poetry, and art they left behind. It is a scanty history much of which can be inferred by comparing it to live experiences. In the past twenty to thirty years nature has become popular. It is a diverse kind of popularity. There is arm chair enjoyment of movies about birds and penguins whose shots are truly breathtaking (but also a construct of technology). Bird watching has become the most popular hobby in the Untied States. Although often done without much physical effort it has gotten people out of doors and encouraged them to pay attention to nature. There is also a newfound enjoyment of physical effort which can range from mountain biking to skiing glaciers to hikes in the mountains with the latest camping equipment or what is now called extreme sport, such as rocketing down a class five river in a tiny, rolling, one person kayak. Each of these is a kind of reconnection to nature. Preceding these activates were the spiritual nature poets of our day. They not only create paeans of nature but offer nature as a solace for our worldly troubles. Their sentiments are not only offered as therapy, but as inspiration for understanding our place in a larger world. All of these modern activities intersect with what forest monks were trying to achieve but crucial to the monks lives was removing themselves from society with little to protect them. This made them different. While they could not escape the neurochemicals, like endorphins and cortisol, that life in the wild elicited, they sought to conquer them or die trying. Without discounting our lives and sentiments it is interesting to examine this difference. It will give us new insights into the world we live and the struggles we have.

After my encounter with the bear my meditation changed. While sitting on the dock looking landward my alertness increased. It took a while for my heart to stop beating so distinctly. That night my sleep was filled with inchoate fear. So I got up and sat for some time and watched as the fear melted away. Emotions are such curious things. The bear had violated my understanding of distance. Later when I heard stories of other’s encounters with this bear, my sense that its behavior was odd was confirmed. It also occurred to me that it found me strange too. I made the mistake of staring at it with binoculars. It couldn’t see my eyes, crucial to making me human. It must have thought me like C-3PO and wanted to investigate.

In 1977 I was on sabbatical from the University and going through a personal crisis. I sat crossed legged for a month long meditation retreat at the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts. I had never meditated before. After that retreat, I balanced my teaching with a month or two of retreats a year and time spent in the garden growing vegetables. A few years after my initial retreat I had the opportunity to sit with Ajaan Cha, a revered forest monk, during his one visit to the United States. Ajaan Cha strongly influenced me, although at the time I had no understanding of forest practice or its principles.

In the years that followed, during the course of my sojourns in various rural and wilderness places, I found myself meditating more and more out of doors. My life seemed to be drawing closer to nature. Meditating in the woods or on mountains deepened my sense of belonging in the wilds. As my experiences grew, I began to bring what I learned into my classrooms. Ironically, I had to teach mostly by metaphor since the reality of life out of doors was alien to my urban and suburban students.

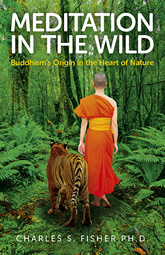

The effort to make clear a certain kind of meditation sent me into the library to find out what I could about the forest tradition which Ajaan Cha represented. It was while doing this research and talking with those few people who had contact with actual forest practice that I began to realize I had been meditating in the spirit of Ajaan Cha, who spent days wandering in the jungles of Southeast Asia. I came to see that I had much rapport with Chinese recluses and Zen Hermits about whom before I had known but little. If I had to claim a lineage of teachers, it would undoubtedly be they. This book and its companion on natural history and meditation, Dismantling Discontent: Buddha’s Way Through Darwin’s World represent explorations of the unexpected extent to which nature informs Buddhist practice. Buddhism, I argue, is indissociable from the realization that nature is the mind’s greatest teacher. Just as Renaissance scientists found they had to study nature directly, and not depend too much on ancient texts, so the Buddhist contemplator can return to nature, not only clearing the mind of society’s delusions, but also, ironically, of confusing and sometimes misleading texts preserved by monastic traditions far removed from Buddhism’s wild sources.

My research was both exciting and frustrating. I found tantalizing anecdotes about the forest traditions, but knew from my own experience that there was much more to these wild ones than had been preserved in books. Because most civilized monks and scholars who preserved or translated the tales of forest monks had little experience with either forest practice or nature, I had to read between the lines. To do so I drew on my own practice and familiarity with nature. Even as I was originally writing this I was aware of the quarter- inch- long wolf spider crawling up the power cord of my computer. She leapt back and forth between cord and computer in a fruitless search for an insect on which to pounce. Would a forest monk leave this spider alone knowing that it might starve in my house so lacking in its prey? Or should I carry the wolf spider outside and let it take its chances there? In the past I have meditated out of doors, sitting silently next to a spider web for days and days until its creator died. Although it may seem ludicrous, I would argue such experiences are profoundly valuable, providing lessons I have yet to fully assimilate. Then there was the time when I was pre-walking a field trip for First Nation youngsters in a dark, woody swamp. As I and my guide approached the edge of the swamp we were greeted by three wolf pups expecting their mother who was off hunting. As my guide fumbled in his rain gear for his bear spray, the pups retreated in the bush. His instinct was self preservation. The little gray wolf wagged its tail like a happy puppy, but a black one had eyes that burned with a wildness which riveted my attention as it backed away. I simply wanted to sit with these beasts of the woods as a forest monk might have, harmlessly sharing both the familiar and the wild, forsaking self-defense in order to learn the meaning of life and death.

One of the purposes in writing this book and its companion on natural history and meditation, Dismantling Discontent: Buddha’s Way Through Darwin’s World, is to speak to meditators about the traditions that some only vaguely understand. Like my students, most meditators are only dimly aware of how nature operates and how much some of what they practice was developed in environments much closer to nature than we now have available to us. How did the recluses and forest monks pioneer the practice of meditation in the wilds? This question seems more than pertinent for people now so interested in Buddhism, nature, and how the two interrelate. I emphasize that because of how we live and what we believe: we have many illusions about nature; and meditation is often presented without the context in which it developed. The forest monks are perhaps the best example of seekers who know how to see and express the silence that is inherent in the flow of a nature completely indifferent to human aspirations. By stepping out of the illusions created by civilization, they were able to observe how nature teaches Buddha’s lessons.

My goal is for readers to gain an appreciation of the forest tradition. You may try sitting quietly out of doors wherever you can find a bit of silence to experience first hand your mind embedded in the ever-changing natural context. I firmly believe that tasting a bit of forest practice can change how one understands our world. This in turn may help in enabling us to live in it with more love and less harming. Meditating on nature may permit us to achieve something like oneness with nature—both nature within and the nature around us with which we have tended, over the course of civilization, to lose contact.

*Photo of Ealue Lake from Wade, Davis, The Sacred Headwaters by permission of the author.