The Zen Hermit, Ryokan, called a furabo or wild scarecrow. |

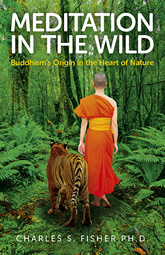

Because the technical demands of e-books preclude them, some illustrations for Meditation in the Wild are displayed here.

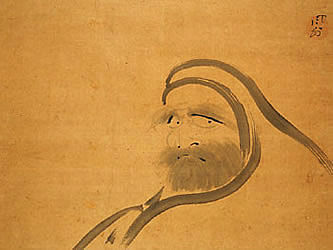

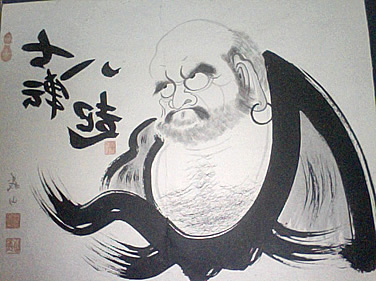

Bodhidharma

Chapter 3. Chinese Recluses:

Page 116 ff.

The First Patriarch of Chan was Bodhidharma, and the myths which surrounded him gave flavor to the tradition he founded. Although Bodhidharma seems to have been a real person, most stories about him are of questionable authenticity….

Bodhidharma cut through the civilization he landed in to find a more grounded reality in the wildness of practice, where behavior was not bound by Confucian civility, the recitation of texts, or the theology of scholars. Practice was meant to penetrate to the essence of existence. Bodhidharma was crude, like the nineteenth-century natural historians’ image of nature driven by survival of the fittest. As Tennyson put it, “Nature, red in tooth and claw.” Pictures of Bodhidharma show him sometimes with a ferocious grimace and other times with a mournful expression. He represents a confrontation with life and death laid bare of the protections of civilization.

1 1 |

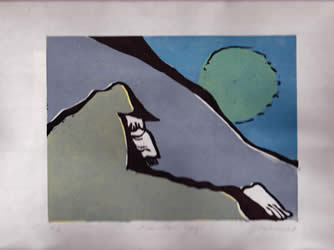

2 2 |

3 3 |

4 4 |

5

5

6

6

Images of 1, 4, 5 and 6 of Bodhidharma are public domain works of art. Such reproductions are in the public domain in the United States. Image 2 is a woodcut print reproduced by permission of the artist Judith Winograd. Image 3 is by permission of the owners.

Sessho

Chapter 3 Chinese Recluses:

page 142 ff.

Sesshu Toyo, (1420–1506) said: “I went to China with the thought of receiving instructions from masters, yet I found no masters but the mountains and waters of China.” Sesshu’s painting, The Long Scroll, is considered one of the major works of Zen or Chan nature painting. In it there are stark rock formations with mist and trees jutting up from the barren landscape. Sesshu painted The Long Scroll from the sketches and memories he had of his trip to China 18 years earlier, when he was so impressed by the Chinese landscape. The scroll, scholars have noted, represents the Zen themes that rocks, trees, mountains all have Buddha-nature and that humans are insignificant in this larger world. When I look at the scroll I do so with American eyes influenced by the Lone Ranger galloping through the seeming emptiness of the American West. On first glance I see dramatic pieces of landscape, apparently inhospitable to agricultural or domestic pursuits, situated in remote areas, which require hazardous journeys to get to them. The hilly background of the scroll strike one as far away in the wilds.

Closer examination reveals something quite different. Although the scroll progresses through seasons rather than through space, each of the seeming wilder parts is either situated between villages or structures of humans or has within them the infrastructure of society. In one direction the pictorial sequence of the scroll shows a steep hillside with steps carved out of rock on an excavated ledge (representing years of labor), a walled town under mountains, and a steep, scraggly treed hillside, again with steps carved out of rocks on the occupied side.

Two people are ascending the steps at the base of which appears to be a cave with lots of people and an inn where there is a celebration going on. Then there are more hills with a path ascending to a temple, sheer cliffs, and a curved Chinese-style stone bridge over a stream. Although most of the scenes in the scroll are pictured below misty mountains, which suggest wildness, the foreground is almost always punctuated with a village, temple, or well-worn human-constructed pathways. It does not feel nearly as remote as an American National Park, with concessions at its base and groomed trails leading away into what might be weeks of hiking in woods and mountains without coming upon another facility. The network of inns and hostels that the government or Buddhist orders erected every 10 miles or less across the Chinese countryside is frequently portrayed in Sesshu’s landscape. He depicts a nature void of nonhuman animals.

Reproductions from The Long Scroll come from an old uncopyrighted Chinese reproduction of “the long scroll.”

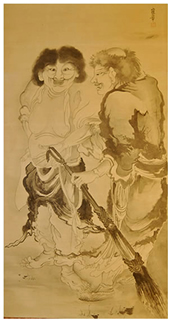

Han-shan and Shih-te

Cold Mountain, a seventh-century recluse, bore the name of his dwelling place. One of his associates, Pickup, Shih-te, was the janitor or cook in a monastery who would supply Cold Mountain with scraps of food when he came to visit. The two are often pictured making fun of the monks. Cold Mountain is dancing and Pickup is sweeping the monks out of their conventional, stuck places. In one painting he is emaciated, with tattered clothes, birch bark cap, and wooden clogs. He may have had a limp. In other paintings he is fat and jolly. The challenges of life out of doors dominate his life. Cold Mountain and Pickup embody Chan irreverence.

Cold Mountain: there’s no through trail.

…

If your heart was like mine

You’d get it and be right here.

… A recluse needs to be willing to live with:

Thin grass does for a mattress,

…

Happy with stone under head.

The poems are respectively from:

Han Shan (1969). Cold Mountain (G. Snyder, Trans). San Francisco: Four Seasons. no. 6.

Han Shan (1983). The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain (Red Pine, Trans). Port Townsend WA: Copper Canyon Press. no. 9.

Permission to reprint for Meditation in the Wild granted by the publishers. Their reproduction here falls under the doctrine of “Fair Use.”

To my knowledge the reproductions of Han-Shan and Shih-te or Kanzan and Jittoku, in Japanese, are in the public domain.

The destruction of the landscape of forest monks.

p.227 ff.

Between 1951 and 1971 the United States spent more than $3 billion in Thailand financing military and strategic rural development. A goal of American aid was to change Thai village subsistence farming to commercial agricultural production. This was accompanied by greater extraction of timber. The percentage of forests in Thailand went from 51% in 1961 to 19% in 1988. The acreage in farming exploded. Thirty large dams were built, flooding thousands of acres. A number of golf complexes were built on forest land. In the Northeast development proceeded apace. Most of the hardwood forests in the Northeast were cut down.

The Northeast was 41% forested in 1961 as compared to 14% in 1988. The first paved road to the Northeast was finished in 1957. Then followed gravel roads into the interior. In the late 1960s the Friendship Highway was completed to the far reaches of the Northeast, tying the entire area together by a network of paved roads….

In addition to the political impact of the war in Vietnam that made wandering in Thailand impossible, the forests themselves began to vanish at an exponential rate and with them the wildlife that lived there. By 1970 wild boar had vanished. Tigers were last seen at a forest hermitage in 1972. Between 1958 and 1988, 88% of the forests of Thailand were destroyed. Pictures of where forests stood now show mile after mile of farms. In 1988 there were huge floods and then student protests about environmental destruction. These led the government to cancel all forest concessions. Despite this, logging continued, either because of government corruption or small time illegal cutting. Since the mid-1970s, the forest monks have become so popular that patrons began to protect the woods around their wats. These woods remain some of the only unaffected forests in Thailand, although they too are subject to illegal harvesting….

By 1956 one forest monk found himself offered rides while walking along roadways, and many of his students were not hardy enough to keep up with him. When forest monks wandered during the dry season the shade of the trees was an important protection. With large trees harvested from those forests which still existed and trees removed from rice fields, exposure to the sun made wandering more arduous, if not impossible. Also walking down roads with speeding vehicles became downright dangerous.

By permission of Luke Duggleby/www.lukeduggleby.com This photo was taken in Cambodia where all the same things which happened in Thailand earlier are now happening. The monks are protesting the destruction of a forest.

Copyright © 2014 Dr. Charles S. Fisher

The contents and images on this page may not be reproduced, mirrored, or republished.