Osho, the Ranch, and Nature*

by Anand Charlie (Charlie Fisher)

November/December 2014

Vol. XXVII no. 6

Pradeepa asked me why Osho is not cited in my recent book, Meditation in the Wild, which examines meditators who, since the Buddha, went off into the woods to practice. She especially wanted to know why I didn’t mention Osho in the sections on Zen. I have no idea why, because I do refer to Osho/Rajneesh in my last book Dismantling Discontent, and I used Osho’s beautiful discourses on Zen in in the university courses I taught on meditation over the years. There I did Kundalini and Dynamic Meditations with my students, something I could have easily been fired for doing if someone had complained. Despite the oversight in my book, my time on the Rajneesh Ranch in Oregon profoundly influenced my understanding of meditation and nature.

In the fall of 1980, suffering from what is called Zen sickness, I found myself in Mumbai sitting at dying Nisargadatta’s feet.** He referred to followers of a guru as dancing to the tune of the tail that tied a guru to the Earth, i.e., somehow followers lived the least developed part of the guru. Nisargadatta’s tail was his penchant for talking: if we all left, he would stop talking and embrace death because his body was entirely worn out. He alluded to Osho in an ironic way. I left to let him die and went to Pune, which was just the medicine I needed for my Zen disease.

And two years later, I was on the Ranch, which was even better medicine. I spent all together one and half years on the Ranch, going back to teach university in between six-month stays. On my second sojourn I worked as a cowboy on the fencing crew. I don’t know what everyone else was doing but we were the Ranch. It was one of the happiest times of my life. Twelve hours a day out on the range: cows, horses, four-by-fours. I had homesteaded in northern Canada and counted trees in the jungles of Central America but always with a sense of separateness. I love the outdoors. I had a profound realization of the fragility of existence and the armor of civilization after almost dying on a canoe trip In the Canadian Arctic. On the Ranch I walked the hills, unrolled spools of electric fencing, munched the grasses to see what the cows did and didn’t like, watched coyotes and deer, but I was never alone, and there were women, who had been absent in most remote regions I had inhabited. You could hug people, dance, and meditate in Buddha Hall.Was this all Osho’s shadow?

It was Osho’s discourses that brought tears to my eyes in the kitchen of my little farm in New England and led me to Pune. Then what I experienced in Pune drew me to the Ranch. Two anecdotes: One day at Cow Camp, the fencing crew’s work station in the hills, I was by myself building a cover for a pump that Osho would pass on His daily drives. I looked up at Coyote Hill next to Cow Camp and realized that since I had come to the Ranch I hadn’t felt alone, a feeling that has haunted most of my life. The realization was mind-stopping. And then later we were separating the herd, checking cows for pregnancy; those not pregnant would be sold off. Cows were let into a pen with multiple gates, herded into a cow crush where they were held tight so someone could insert an arm to check the womb, and then sent into either the keeper or the selling pens. It was dangerous working in the pen with the cows. You had to be totally alert. One member of the crew lost a kneecap to a sideways kick. It was an overcast day, toward dusk. The pens were muddy. I was in the pen directing cows one way or t’other. No thoughts, just action, when my mind came to a complete stop. I can still see the exquisite smooth brown texture of mud mixed with cow shit. I was happy. No bending forward or back – nothing else existed. A satori? Who knows? Such moments have happened since but none with such a complete blending of my being and my surroundings.

When I read the poems of Ryokan, the most, accessible Zen hermit, I see similar experiences from his life in the woods. Osho had a deep appreciation of such Zen Masters. For years after the Ranch closed, I would dream about walking the hills, about five of us stuffed into the crew cab of a pickup, a little like a roving Encounter Group, and Neehar lecturing us on how much more important it was for us to get along than to do the work we were doing. I worked with a man with whom I never would have connected in the outside world. He had been an army counterintelligence operative. Once we laughed so hard that he threw out his shoulder bonking in a barbed wire fence post. Although ancient Indian forest renunciants, Chinese recluses, and Zen hermits sometimes had dharma friends, they were not to get attached. As the Rhinoceros Sutra instructs, the seeker should “wander solitary as a rhinoceros horn.” Forest practitioners’ insights grew out of their solo connection with nature. Those of us privileged enough to spend our days wandering the hills above the John Day River had the best of both worlds: dharma friends to whom attachment was inevitable, and nature.

In Chapter 3 of A Sudden Clash of Thunder, Osho says: Such a vast Universe, running so smoothly… Look at the stars, look at the change of seasons; rivers running from the Himalayas to the ocean, clouds coming and showering. Watch nature – everything is running so smoothly! Why not become a part of it?

Was Cow Camp, the Ranch – was the whole experience in Osho’s shadow or His light? I don’t know.

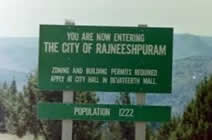

* Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh (1931- 1990) changed his name to Osho in 1989. Born a Jain, he was a professor of philosophy until his radical ideas led him to travel India teaching. In the early 1970s Westerners were drawn to him and he settled down with them as disciples in Mumbai, opening an ashram in Pune in 1974. There thousands of Westerners did his active meditations and took part in therapy-like groups which were a synthesis of his spiritual ideas and humanistic psychology (including things like Encounter, Rebirthing, and Gestalt about which he learned from Western therapists who were drawn to him). His brilliant discourses on all the major religious traditions can be found in dozens of published volumes. In 1981 he moved to a remote ranch in eastern Oregon to form a utopian spiritual community. It lasted until 1985 when the state and federal governments suppressed it. There are any number of books about the ashram and the ranch.

** Zen Master Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768), one of the founders of Rinzai Zen, meditated so intensely on the Mu that he had a nervous breakdown. He found relief from Esoteric Taoist healers.

Sri Nisagardatta Maharaj (1897-1981), known as the bidiwala of Bombay wentoff to find his guru in 1936. His guru told him to go home and attend to the sense of “I am.” His sayings are preserved in a book entitled, I Am That.

Copyright © 2014 Dr. Charles S. Fisher

The contents and images on this page may not be reproduced, mirrored, or republished.